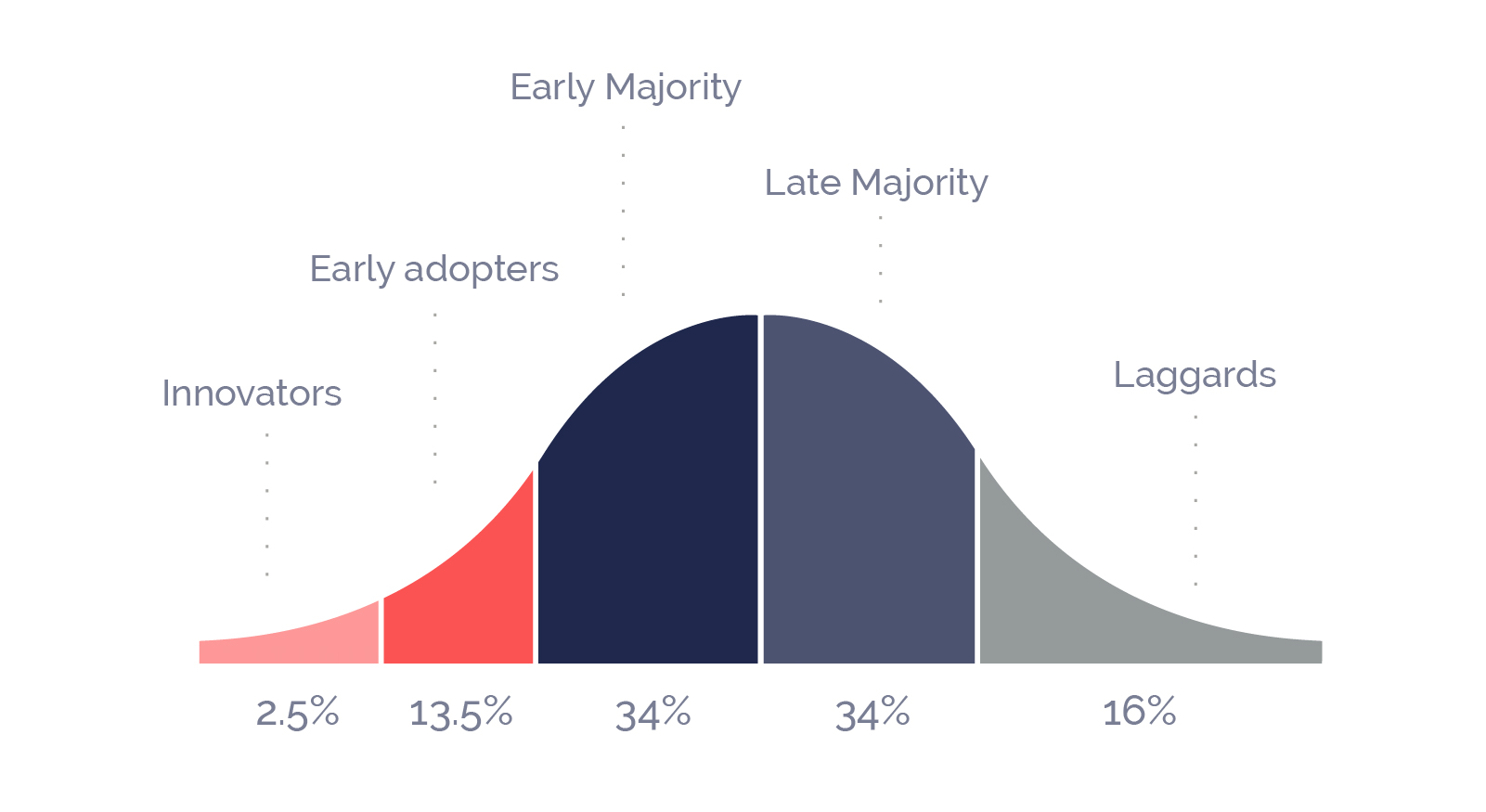

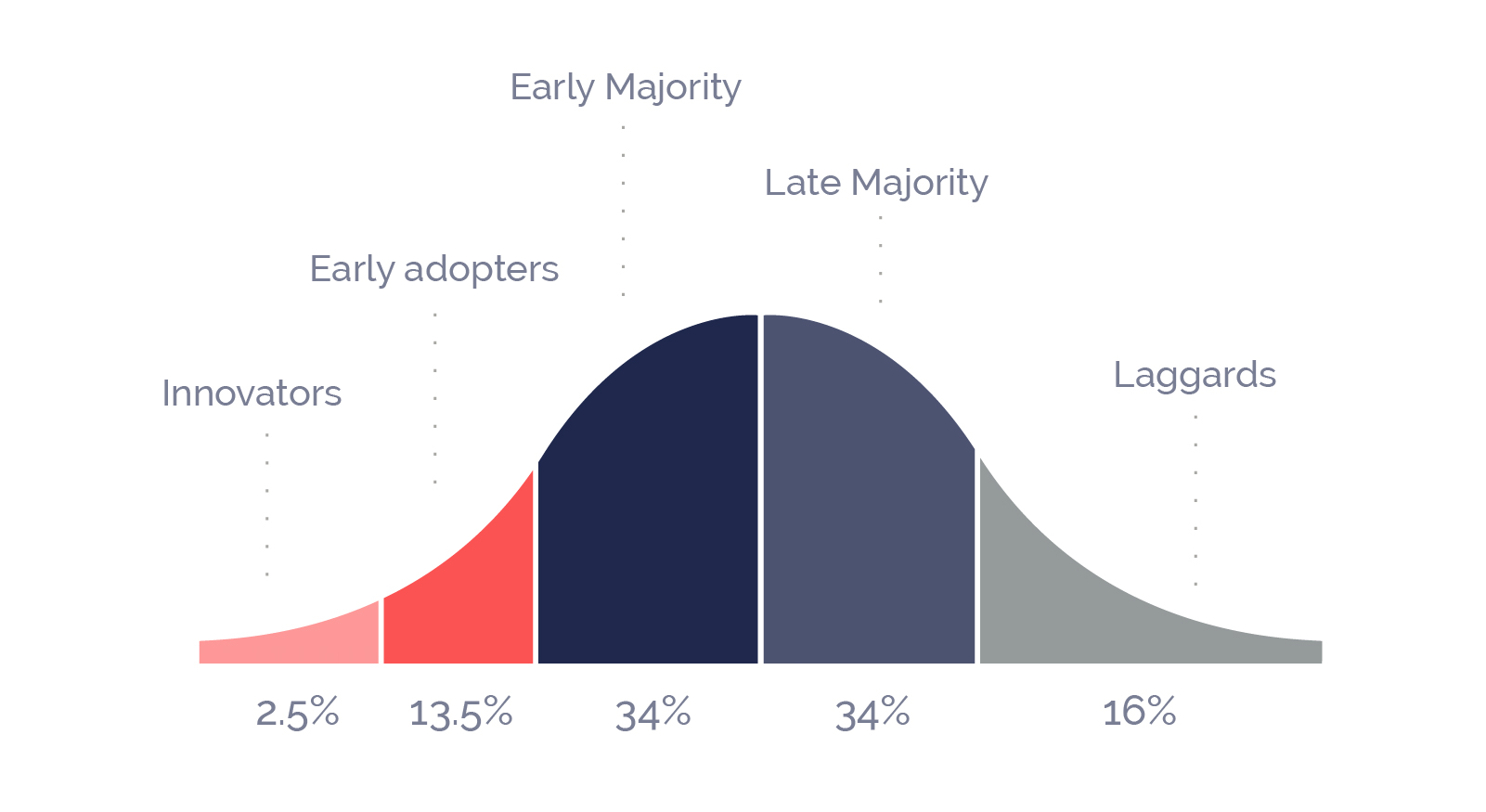

If you’re a founder or a marketer at a start-up, it’s likely that you’re aware of the ‘diffusion of innovation’ curve, even if you didn’t know its name. The model shows how society adopts innovations:

It’s a well-known theory that has been part of the start-up landscape since Everett Rodgers first included it in his seminal work ‘Diffusion of Innovations’ in 1960. When a model has been around for this long, it may be tempting to disregard it as outdated. But it’s still just as relevant today as it was 57 years ago.

In this blog – the first in a four-part series about fintech growth – we’ll look at what the model tells us about how people adopt new innovations and what fintechs can still learn from it in 2017.

The Diffusion of Innovation Model

First, a quick explanation of the model itself. The model states that a population can be broken down into five different segments, based on their propensity to adopt a specific innovation:

- Innovators

- Early adopters

- Early majorities

- Late majorities

- Laggards.

Innovators – 2.5% of the population

Any adoption process begins with a small number of imaginative innovators. They often expend great time and energy on exploring new ideas, and are equally quick to try and quick to drop new products or services.

At just 2.5% of the population, innovators’ fixation on the new can make them seem out of step with the more pragmatic majority, but no change can begin to take place without their energy and commitment to trying new things.

These are the people who are currently investing in Ethereum cryptocurrency and have been riding the Bitcoin high for the past 12 months (at the time of writing!).

Early adopters – 13.5% of the population

Once the benefits of an innovation start to become apparent, early adopters jump in. They’re on the lookout for a leap forward in their lives or businesses and are quick to make connections between clever innovations and their own needs.

Early adopters love getting an advantage over their peers and they have time and money to invest. They tend to be more economically successful and informed and hence more socially respected. Their seemingly risky plunge into a new activity gets people talking – others watch to see whether they prosper or fail, and start talking about the results.

While a great source of potential advocates and free promotion, early adopters are vital for another reason. They can become an independent test bed, ironing out chinks and providing feedback to help adapt the innovation to suit mainstream needs. For fintech start-ups, it’s absolutely essential to ensure that early adopters are consulted and their feedback listened to before trying to scale towards early widespread adoption.

These are the people who are currently incorporating peer to peer lending into their investment portfolio.

Early majority – 34% of the population

Next in the model is the ‘early majority’ – a pragmatic sector who are comfortable with progressive ideas, but who won’t act without solid proof of benefits. They’re wary of fads and want to hear that something is “industry standard” before they commit.

Consumers in the early majority want minimum disruption and negligible learning time. They won’t take the time to learn how to use a new product because they are too busy living their life or running their business. Any new product or service needs to offer a markedly better solution straight out of the box.

These are the people who are comfortable using new FX transfer services to transfer money overseas, rather than relying on their bank to do so.

Late majority – 34% of the population

The late majority are conservative pragmatists who intensely dislike risk and are uncomfortable with new ideas. Their main driver to actually adopt a new innovation is not because they can see its benefits, but rather due to a fear not fitting in.

For the late majority, social proof is vitally important – they want to see that people just like them are using the service and find it indispensable.

These are the people who are just starting to bank on their mobiles using apps, rather than their desktop.

Laggards – 16% of the population

Laggards are those who hold out to the bitter end – who see a high risk in adopting a particular product or behaviour.

Laggards are not a sector that start-ups are likely to engage. However, some of their ‘glass half empty’ concerns may be valid and worth taking into account to bake into a product or service early on, to ensure that the laggards worst fears aren’t realised.

These are the people who are reluctant to install their bank’s app onto their phone, because they are worried about security risks.

What can fintech organisations learn from the model?

The key thing to take away from the Diffusion of Innovation model is that it is both a model of change and a model of consumer behaviour. However, rather than a change OF consumer behaviour, the change is actually the evolution of a product itself – adapting it to become a better fit for each group.

Progressing through the model and using feedback from early adopters is a key part of getting product / market fit right before committing resources to growth. Premature scaling is the number one cause of failure, and start-ups often need two to three times longer to validate their market than founders expect.

But the model presents another warning for ambitious founders.

When looking at the potential size of a market for a new business, it’s tempting to focus on the whole market. “If we get just 10% of the market, that’s $xxx,xxx per year revenue.”

But accessing that lucrative mass market is incredibly difficult and very few Australian fintech firms have yet achieved it. Only in China have financial start-ups claimed a significant portion of the mainstream market – 35% of the market for digital insurance and payments are currently held by fintechs.

What this means is that start-ups need to be realistic about the value of the market that is available to them at launch. They need to base their initial modelling and predictions on uptake by innovators and early adopters, and ensure that the business is sustainable on that basis. While mass market adoption is something that should be considered a possibility and something to aim for, it should not be relied on for the business to be a going concern. Doing so is a recipe for rapid failure.

This realisation of the importance of early adopters to product development and the early sustainability of a business is why the Diffusion of Innovation model is just as relevant for fintechs in 2017 as it was for fledgling businesses in 1960.

In part 2 of our series of on fintech growth, we’ll look at how to connect with innovators and early adopters. We’ll cover how to validate your model with them and how to ensure a constant flow of feedback to improve your business and create advocates.

In parts 3 we’ll look at finalising product market fit and why fintechs should focus on their concept, not their product. And finally, in part 4 we’ll discuss how fintech start-ups can cross the gaping chasm between the early adopters and the early majority – an Evil Knievel-like leap that very few fintechs in Australia have yet managed.