If you were to focus on headlines in the AFR, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the end is nigh for financial advice in Australia.

The perfect storm of the impact of the Royal Commission, changes in remuneration models and death knell of vertical alignment suggests that Wealth as a business model is a paper tiger. The banks certainly seem to think so, with three of the Big 4 exiting or planning to exit financial advice. For those still in the game, the major players are resetting and shedding advisers in record numbers.

While the story appears bleak, the need for financial advice remains. The question is, how does an industry traditionally adverse to change adapt and thrive despite these obvious headwinds?

The answer lies in the advice experience. That’s how we save advice.

Valuing advice

The bane of the lives of wealth business strategist and insights teams has been the desire the measure the ‘value of advice’. This amorphous term requires us to consider so many rational and emotional considerations, it’s no wonder that it’s proven the Holy Grail of consumer understanding.

With that in mind, I’ll make no attempt to qualify the value of advice, other than to clarify the driver for wanting to understand value – wealth firms want to know how much they can charge their clients.

And that’s the core of the problem. Financial advice is generally not considered as a professional service in the same way as other services for which we accept a fee being paid, e.g. lawyers and accountants.There are many reasons for this. One fundamental driver is that historic remuneration models have been opaque, allowing for advisers to be paid on a commission basis to deliver advice. For many clients, while fees are disclosed, it ‘feels’ like the advice is free, as they rarely make a direct payment.

Now clients are being asked to pay a fee and they don’t like it. Even though they were paying for the service before now. They just didn’t experience the negative connotations of paying a bill, of seeing money exiting their accounts.

The trusted adviser?

Compounding perceptions of value are perceptions of trust.

The repercussions for financial advice from the Royal Commission are far reaching. The Commission shone a very unflattering light on institutional practices, remuneration models and specific wealth management firms.

Wealth became a lightning rod for the press and the centre of attention of the Commission. A flow on effect appears to be an impact on consumer trust of financial advice. However, based on recent ASIC research, trust in financial advice is not at critical levels, it’s just (not unreasonably) taken a big hit.

Interestingly, those Australians who had recently experienced financial advice were much more positive towards the segment. With only 27% of Australians having actually experienced financial advice, it appears that the headline lack of trust is more based on perception than actual experience.

Either way, if advice is to position itself as a valued professional service, trust is a commodity that it must trade in and right now, it’s in short supply.

Without rational foundations, it’s a house of cards

Let’s take a second to consider the wider context of the Commission.

Wealth was a big focus, but so was banking, so was insurance. So why then, of all the segments reviewed in the Commission, has wealth taken by far the biggest hit?

We’ve seen major institutions shedding both their wealth business and large numbers of advisers. Most importantly, we’ve seen the value of AMP, Australia’s biggest wealth manager, plummet, record outflows and losses. It faces an uncertain future, unlike retail banking and the other segments reviewed in the Commission.

And we believe we know why this may be the case. The experience of financial advice has few rational anchors on which to build an ongoing dependence. Unlike banking, which delivers transactions that empower us in our day-to-day lives, advice is low-touch, leaving few opportunities to build trust or loyalty through meeting rational needs.

It’s this traditional wealth experience that we believe could be a root cause in both the lack of trust and perceptions of value.

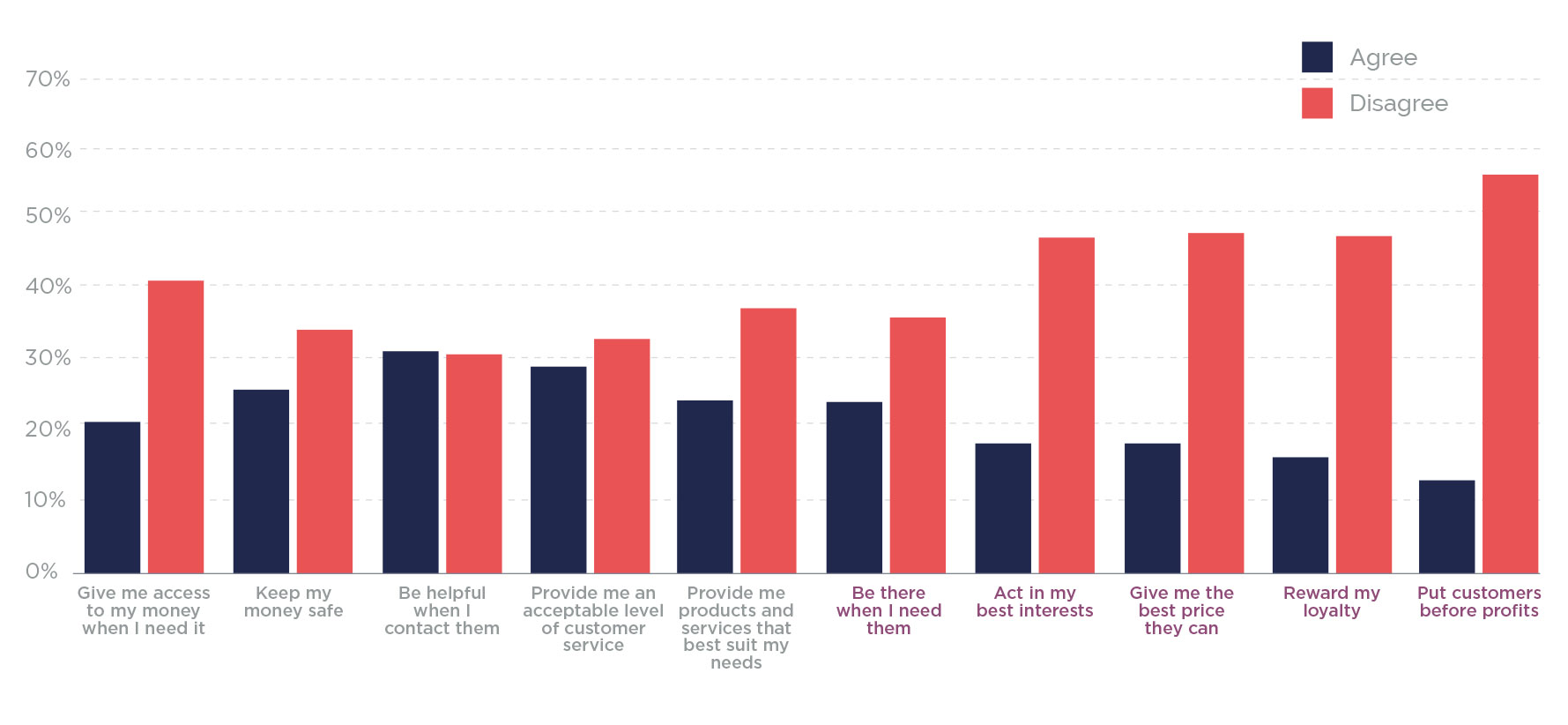

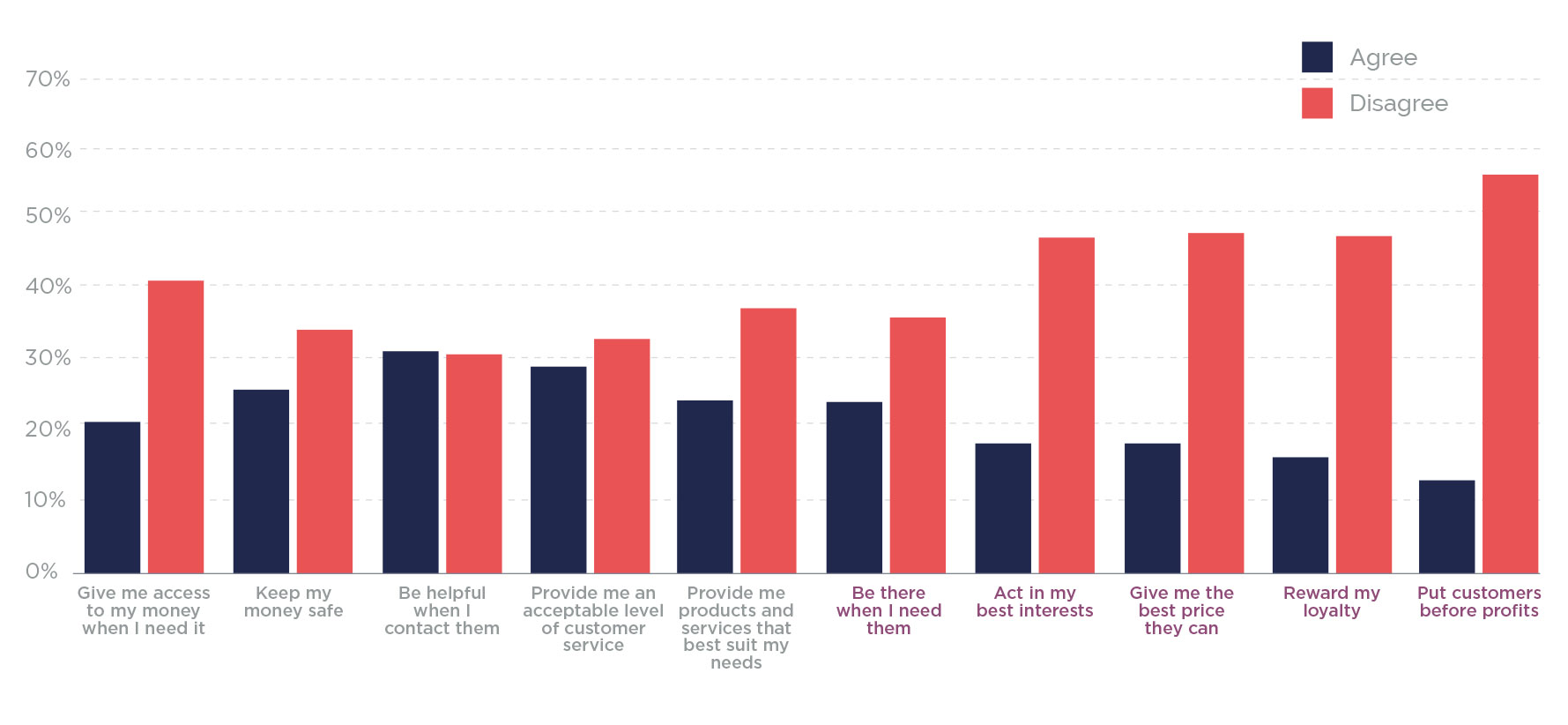

This year’s Financial Marketing Survey results showed us that consumers rate financial advice poorly for both rational and emotional factors.

The Big 4 banks, which also scored poorly for emotional factors, did far better when we asked about rational factors. We believe this comes from the experience that most of us have with our banks. It’s one of frequent transactions, delivered through an increasingly user focused digital experience. The banks, whether we trust them or not, deliver on our day-to day expectations.

The Big 4 banks, which also scored poorly for emotional factors, did far better when we asked about rational factors. We believe this comes from the experience that most of us have with our banks. It’s one of frequent transactions, delivered through an increasingly user focused digital experience. The banks, whether we trust them or not, deliver on our day-to day expectations.

Financial advice does not. Broadly based on an annual cycle of a single review, financial advice is generally a low-touch experience, with long-term outcomes that provide little in the way of rational reward.

Without an experience that we can see and feel making a day-to-day difference in our lives, how can we expect to see financial advice as a trusted professional service worth paying for?

If advice is to be saved, then this is the fundamental issue that needs to be addressed.

Building on a wealth of experience

How do we transform the advice experience into one that allows consumers to see the ongoing benefit and value of advice?

Clearly, relying on face to face advice delivered around an annual review is not enough. This traditional model needs to evolve to meet the needs of customers who consume information and interact with their finances daily.

It appears that AMP’s new strategy may be starting to address some of these issues. By focusing on delivering an experience that embraces a mix of adviser and digital channels, AMP may well create a more tangible and rewarding experience, one that may meet the increasingly demanding needs of modern consumers.

The truth is that Australians need help in managing, growing and protecting their wealth and based on our research and insights, we’ve identified three broad strategies for keeping Wealth relevant:

1. A lifetime of experience, delivered every day

Financial advice has evolved over the last 10 years to increasingly focus on lifestages. This is all very well, but this approach is often still driven by product rather than experience.

Before financial advice can truly thrive, wealth managers need to consider designing and building an experience that allows for a flexible, ongoing interactions, that puts customers in control of the experience, whilst receiving the benefit of expert advice.

2. Commoditise advice

Not every advice scenario requires complex face-to-face advice. For many Australians – the 73% that have never received financial advice – cost and an apparent lack of complexity in their financial circumstances are barriers to considering advice.

If the industry can create commoditised solutions, delivering guided outcomes for simple financial needs and accessible to everyone, we may well see broader advice uptake.

3. Personal, not just personalised

There is clearly also still a role for a personal, high-touch advice relationships for those with complex needs, but these clients are usually affluent and used to paying for professional services.

They value the role that advisers play in their lives and the personal relationships they build. Another opportunity for wealth to remain relevant while delivering at scale is to replicate this model through creating digital empathy and personal (not just personalised) digital experiences, which support face-to-face advice.

The Big 4 banks, which also scored poorly for emotional factors, did far better when we asked about rational factors. We believe this comes from the experience that most of us have with our banks. It’s one of frequent transactions, delivered through an increasingly user focused digital experience. The banks, whether we trust them or not, deliver on our day-to day expectations.

The Big 4 banks, which also scored poorly for emotional factors, did far better when we asked about rational factors. We believe this comes from the experience that most of us have with our banks. It’s one of frequent transactions, delivered through an increasingly user focused digital experience. The banks, whether we trust them or not, deliver on our day-to day expectations.